The New York Financial Writers' Association History

Founded in the maw of the Depression and the shadow of war, the New York Financial Writers’ Association has survived and prevailed with a little help from its friends and a few laughs along the way. Members of the New York Financial Writers’ Association have been covering the ups and downs of business and finance around the world for more than 80 years.

The Association was founded in the depression — on June 15, 1938 — on the eve of World War II. Its members have chronicled the advent of the Atomic Age, the Jet Age, and the Electronic Age, as well as the plethora of labor strikes and lockouts, mergers and acquisitions, recessions and booms, and the fluctuations in stock and bond prices. When the Association was founded, the Dow Jones Industrial Average was dragging along at 113.24 on volume of 344,620 shares on the New York Stock Exchange. On June 15, 1998, the NYFWA’s 60th anniversary, the Dow was at 8,627.93 and volume that day was 582 million shares, a volume that would have been impossible to handle 70 years ago when stock trades were tabulated by hand. Now they are handled routinely by computers. Over the past 80 years, members of the NYFWA have provided vital information of the day and have contributed to a better understanding of local, national and international events that have affected the lives of every man, woman and child in the world. Americans do not live in a cocoon. What happens in Asia, Europe, and Africa affect this nation’s economy just as surely as the steps taken in Washington affect others. It’s the responsibility of NYFWA members to report and explain these events as they happen As world economies and markets have experienced unprecedented growth, so has the Association.

From a small group of 45 members, the Association’s has expanded into the hundreds. And its members can look back over the years with pride in their contributions to business and financial journalism. In the United States, the economy was still in depression, and unemployment hovered around the 15 million mark. The market crash of 1929 and the subsequent economic relapse of 1937-38 had wiped out more than $36 billion from the value of stocks listed on the New York Stock Exchange. The public had lost confidence in the nation’s financial community and this carried over to the financial pages. Financial journalists were deeply concerned about their image in 1938. At a party one night at the New Yorker Hotel, a group of financial editors and writers discussed forming an organization that would help raise the professional standards of financial journalism. The participants were John P. Broderick of the Wall Street Journal; Elliott V. Bell and John G. Forrest, The New York Times; Charles A. Donnelly, New York World-Telegram; George A. Phillips, Associated Press; C. Norman Stabler, New York Herald Tribune, and Elmer C. Walzer, United Press.

The journalists liked the idea of their own organization and sounded out leaders in the financial and business community, who gave them strong encouragement. Buoyed by this reception, approximately 55 members of the financial press met at the New Yorker on June 15, 1938, to found the New York Financial Writers’ Association. The founders were inveterate optimists, but even in their most sanguine moments they could not foresee what their labors would bring forth. After a shaky start that saw the organization teeter on the economic brink for a year or so, the Association grew into a robust group with more than 350 active, life and associate members. At that first meeting, as one founder later recalled, “We ate bologna sandwiches and hot dogs and drank a keg of beer while electing Elliott Bell our first president and wrestling with the bylaws, which set strict standards for membership.” Other Association officers in the founding year were Charles Donnelly, vice president; William Lyon, treasurer; and Walter Woodworth, secretary. The standards for membership were strict indeed. Only financial writers with three years experience on recognized newspapers and wire services were eligible. And the word “financial” meant what it said.

In 1938, many newspapers had separate financial and business news departments, each with its own editor. Since they vied for the limited space available, competition between them was often keen, sometimes antagonistic. At first the Association would not accept business writers, and it would be years before active members were allowed to stay in as associate members if they left journalism for related fields. The Association had one thing going for it in the economic morass of 1938 – the support of one of the most powerful banking institutions on Wall Street, if not the world. Thomas Lamont, president of J.P. Morgan & Co., was an early supporter of the Association and he authorized its first checking account, even though it fell woefully short of the bank’s minimum standards. It was probably the smallest account ever at the House of Morgan. Other business leaders who lent encouragement to the nascent organization in 1938 included William McChesney Martin Jr., president of the New York Stock Exchange and later chairman of the Federal Reserve Board; Harold Bache, head of Bache & Co.; William O. Douglas, chairman of the Securities & Exchange Commission and later Supreme Court Justice; and Wendell L. Wilkie, president of Commonwealth and Southern Corp., and 1940 Republican presidential candidate. Thus the fledgling organization had some powerful friends.

The next year it would have an official logo, a circular symbol showing a quill and inkwell in front of the Sub-Treasury Building on Wall Street. Designed by William Indelicato of the old New York News Bureau Association, the logo was fashioned out of wood by the head carpenter at the Hotel Astor. But what the Association didn’t have was cash flow. Founded as a non-profit organization, it found that it was less than non-profit – in fact, it faced a financial crisis. To raise some money, Charlie Donnelly, who would later be the fourth president, suggested a satirical show patterned after those produced by the Gridiron Club in Washington and the Inner Circle in New York. The idea was seized upon and a search was launched to find a hotel that could accommodate such a show without charging and arm and a leg. “We had no money and no credit,” a founder recalls, “But we had enthusiasm and a lot of good friends in influential places.” One of those friends would be the Financial Follies’ first angel – Robert K. Christenberry, manager of the Hotel Astor at 45th Street and Broadway, the fabled hotel where Tom Mix once rented a suite for his horse. Christenberry agreed to bankroll the show, paying all bills until the organization could reimburse him from Follies receipts, which it did to the penny. Christenberry even chipped in and bought a table.

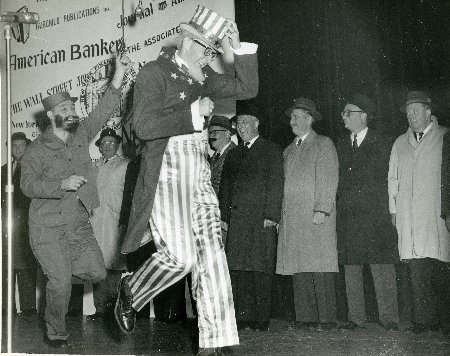

To keep costs down, members helped to make the scenery and their wives helped sew some of the costumes. By such frugalities, the ticket price was held to $10 per person, still a sizeable sum in 1938. At rehearsals, members chipped in to buy the beer, and nobody went home until it was consumed. The result was the first Follies, held on December 16, 1938. Since then dozens of leaders in business and finance, labor and government have attended the annual lampoon produced, written and performed by members of the Association. The only professionals involved in the first show were George E. Price, an actor turned broker who served as the director; and Floyd J. Hynes, who was the musical director of every Follies from 1938 through 1964. After rehearsals, Floyd would hang around providing musical accompaniment on the piano to the keg-killing ritual. Burton Crane, a New York Times writer and erstwhile playwright, wrote original music for the 1938 show, which ran three hours with one intermission. The show has been shortened in recent years, and now runs less than one hour. The cover of the 1938 program featured a stock certificate – a real stock certificate. There were plenty of them around from companies that had gone belly-up in the Depression. There was even a shop in the Wall Street area that did a brisk business selling these worthless certificates to optimistic investors who hoped that some defunct companies might rise from the ashes. The Association, harboring no such illusions, bought 1,000 stock certificates. The problem, as soon was evident, was that they were of different sizes and couldn’t not be used with automatic binders. All 1,000 had to be individually stapled. The 1938 program in the Association’s archives features a stock certificate made out to a C. Merrill Chapin Jr., for 250 shares of capital stock. It was dated February 9, 1926. That was a time when Catholics had to eat fish on Fridays, so the ecumenical menu included both aiguillette of gray sole Marguery and noisette of lamb Renaissance. A decade or so later, the Association received dispensation for its guests to eat meat on Follies Friday from Cardinal Spellman. “We didn’t fool around,” one founder later recalled. “If we didn’t get dispensation from the Cardinal we would have gone to the Pope.” Nobody, from the president of the United States on down, was exempt from the barbs of the Scribes aimed at the Pharisees at the first Follies.

The first skit, called “Paging UAL,” needled Floyd B. Odlum. Another, “Seven Saviours,” gave the gaff to Neville Chamberlain, Edouard Daladier, Benito Mussolini, Joseph Stalin, Adolf Hitler, Franklin D. Roosevelt and the famous New Jersey power broker, Frank Hague. The audience was a Who’s Who of business and finance, many of whom had arrived aboard their private railroad cars, which were on display at the Pennsylvania Railroad’s Sunnyside yard. In addition to Willkie, Martin, Douglas, Bache and Lamont, there were Lowell Thomas, Arthur M. Andersen, Alpheus C. Beane Jr., T. Rowe Price, Jacob Javits, Eugene C. Grace, Robert R. Young, John L. Lewis, Irving S. Olds, Marriner Eccles, Benjamin Fairless, Edwin S. Friendly and T.J. Ross. In the audience at the Astor were 870 men and one woman – Mae Wolff Stabler, the Association’s first executive secretary. A few of those business brahmins walked out that first night. A handful never came back. They weren’t missed. Fortunately, the vast majority of the audience enjoyed laughing at themselves and the cast, a group of misfits, the likes of which the stage had never seen before. Two men, both great friends of the Association, came back each year knowing they were in for a ribbing – G. Keith Funston, president of the New York Stock Exchange, and Edward McCormick, president of the American Stock Exchange. McCormick, whose exchange was known as “The Curb” until 1953, especially liked the song that depicted the Amex as the place where they “trade in back of the graveyard.” The 1938 show established the Follies as an institution in New York. Highly successful shows followed in 1939 and 1940, when the program looked like a vaudeville poster and carried a message on the inside front cover that pretty well summed up the spirit of the Follies: “Ladies and Gentlemen: Fundamentally, the principles that we stand for are fundamental. Withal it is important to realize that fourscore and seven years ago is worth two in the bush. In this connection, let me say that a stitch in time gathers no moss. And furthermore, it’s a long corridor that has no men’s room…Albeit with mixed feelings let me urge American industry not to burn their bridges before their chickens are hatched. Thanking you one and all, and on with the show.”

The 1941 show, the last until the end of World War II, was held at the Waldorf Astoria on Saturday, November 1, a month before the United States was engulfed by war. The program for that year showed several active members already in military service and the guest list revealed a Sgt. William McChesney Martin in the audience. The show’s finale was a rousing patriotic tribute called, “Our Land.” Patriotic finales became a hallmark of the Follies until the late 1960s. The Follies reappeared on February 23, 1946, again at the Astor, its home until the hotel closed in 1966, when the show moved to the Americana (now the Sheraton Centre), with one stop at the old Commodore. The show was finally moved in 1997 to the Marriott Marquis, in the heart of Times Square. Price directed all three prewar Follies shows. Edmund Tabell, a stockbroker, directed the 1946 show, and Bruce Evans took over from 1947 to 1968. Jerome Goldstein, who started as musical director in 1965, has directed the Follies ever from 1968 to 2004. Laura Josepher took over in 2005 will Jill Brunelle, the music director. Over the years, two men have graciously volunteered to miss the Follies so they could sit backstage and protect the valuables of cast members. Ken Lovelace, who was with the New York Stock Exchange, did it for years. Gil Baker, formerly with the Albert Frank-Guenther Law, was the keeper of the keys in recent years. As the 1940s came to an end, many felt the organization needed more than the Follies to carry out its original mandate. In 1950, an annual picnic was organized and held in the spring at the ITT picnic grounds in Nutley, New Jersey. It is tradition that died out but was reborn with a “Day at the Races” at Belmont Park.

The Association now sponsors a “Hacks vs. Flacks” softball game in Central Park that pits journalists against PR professionals. The Spring Dinner, started in 1952, was renamed in 1996 as the Annual Awards Dinner. In 1975, the Association inaugurated the Elliott V. Bell Award for those who have made a significant long-term contribution to financial journalism. The first award was given to Sam Shulsky of the Journal American, who pioneered the question-and-answer format on financial pages. In 1976, the Association launched its scholarship program by assuming responsibility for the Maurice Feldman award, named after a public relations man much beloved by generations of reporters. The award that year was $500; it has since been increased to $3,000. The Association now gives away $30,000 a year in scholarships. In themore than 70 years that have transpired since its founding, the Association has changed and adapted to the world around it, and has grown in importance along with the world of finance and industry that its members cover. In 1945, the Board of Governors of the Association voted to admit business writers, and also created an associate member classification. The latter action split the Association, with several active members quitting and urging their coworkers to boycott the Association – a drastic reaction in view of the fact that associate members have no vote in Association affairs. In 1972, when the Association admitted women to membership for the first time, there was no similar walkout, although a few prudes wondered how they were going to make those fast costume changes at the Follies under scrutiny of the opposite sex. Somehow, they managed.

*Robert Shortal was president of the NYFWA in 1958-1959